Fast Facts:

Hans Abrahamsen – one of Denmark’s great musical minds – was born on December 23, 1952, in Lyngby, just north of Copenhagen (don’t forget to wish him happy birthday soon!).

He entered the Royal Danish Academy of Music at just sixteen, originally to study the french horn. But a partial paralysis in his right hand forced a change of plans. Luckily, he was also fascinated by music theory and composition.

His international breakthrough came in 1982, when the Berlin Philharmonic premiered Nacht und Trompeten under Hans Werner Henze, who had not only encouraged the piece but also received its dedication.

The orchestra later doubled down on their faith in him, commissioning the now much-celebrated song cycle Let Me Tell You, premiered in 2013 by Barbara Hannigan and Andris Nelsons. The piece quickly picked up prizes. Showing a shimmering Shakespearean snowstorm. And just five years ago, they added his Horn Concerto to the list of world premières.

Some of his teachers were Per Nørgård, Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen, and György Ligeti. The first two (danes) are often linked to what my teacher, Søren Schauser, calls Nordic Nakedness – that uniquely Scandinavian “less-is-more” aesthetic. (Some call it New Simplicity, though definitely not to be confused with the German version.) Abrahamsen’s early works clearly carry the family resemblance.

Stylistically, Abrahamsen’s music balances clarity and mystery. He works with crystalline textures, bare painterly structures, and delicate, fragile melodies, sometimes sneaking in microtonal twists, tiny pitch wiggles, and quiet repetitions. It can sound deceptively simple, but beneath the surface lies a sophisticated and unmistakably personal sound world.

In 2019, his first opera, The Snow Queen – based on Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale of the same name – premiered at the Royal Danish Opera in Copenhagen. Since then, it has travelled to Munich, Strasbourg, and Amsterdam (in concert). On 7 December, it opened in a brand-new production at the Semperoper in Dresden – and yes, I’ll be hearing it next week.

So of course, I had to stop by the composer himself to hear what he makes of it all.

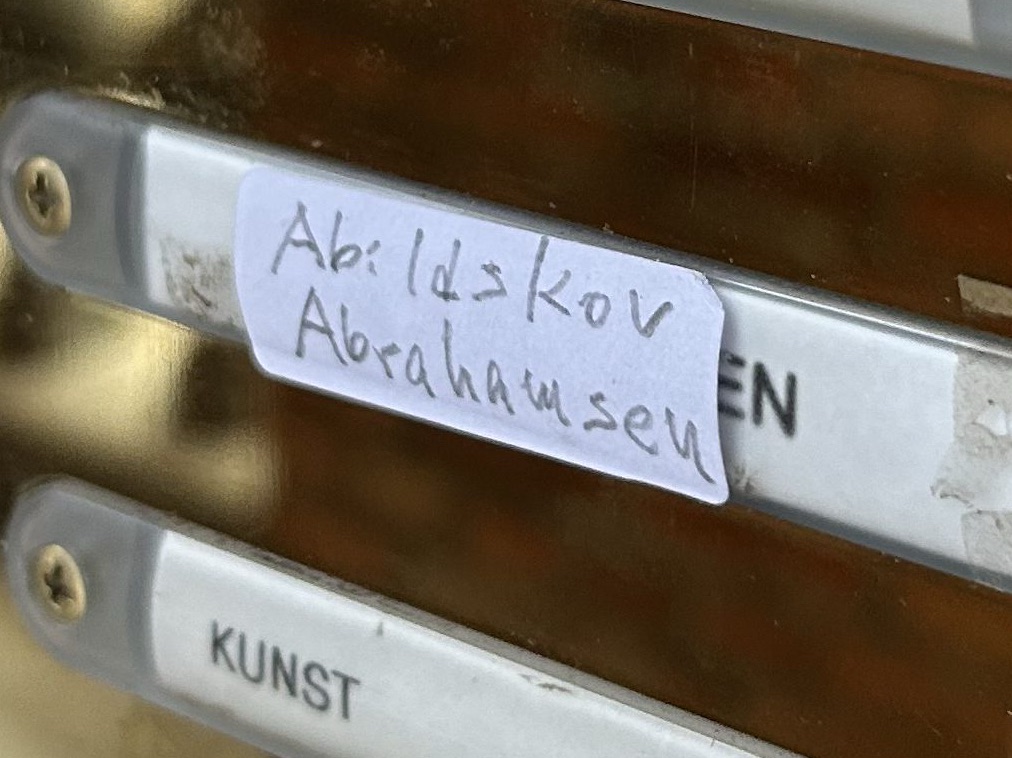

I ring the doorbell. The name Abrahamsen is handwritten on a small scrap of paper, carefully taped over the name beneath. Hans Abrahamsen and his wife have only just settled in. Inside the hallway, cardboard and plastic cover the floor, the air smells faintly of fresh paint, and half-unpacked moving boxes have gathered – naturally – around a black Steinway grand piano. On the music stand: the familiar blue Henle Urtext edition of Chopin’s Études.

Along with a smiling Hans, I’m also welcomed by the other resident of the house – their very affectionate cat, Ella.

In the living room, coffee is poured, cookies appear, and we settle softly on the sofa.

Ice-breaker

Freja Holte (FH): »How did you end up writing an opera?«

Hans Abrahamsen (HA): (thinks for a moment) »That’s a good question.« (We both laugh).

Opera, he says, is a very special genre. Back in the 1980s, when he was in his thirties, he had begun listening more seriously to opera – even circling the idea of writing one himself. But it never quite took off. »I was also, in a way, gearing myself towards writing an opera – but I gave up. I couldn’t.«

FH: »You didn’t quite know where to start?«

HA: »No. It’s that whole connection – between the music, the theatre, and all the different genres coming together.«

FH: »Yes, there are many factors.«

HA: »And so it just stayed there. But very concretely, with The Snow Queen, it came back. I was in my fifties when I wrote the piece called Schnee – snow, in German. I wrote it in two stages, and before the second stage, where I wrote the last four canons, I read a lot about snow – snow imagery, poets who write about snow, and so on.

And it was actually my wife who suggested that I should read The Snow Queen by H.C. Andersen.

I was very, very inspired by it. And there are images from Andersen’s The Snow Queen that actually go into Schnee – or rather, they begin in Schnee. For example, there’s an image in the fairy tale where Kay, after getting the splinter in his eye and his heart, is out in the square with Gerda. Children are playing in the snow. That image… goes directly into my second canon in Schnee. That (Abramsen sings the beginning) pop-up-up-up-up… «

FH: »So was that something programmatic, or more something that inspired…?«

(He answers before I finish the sentence.)

HA: »It’s more the idea of snow dancing. Yes. And if you have snow dancing, then that’s also a reference to Debussy’s wonderful piece from Children’s Corner… at that point, I actually made a libretto for myself. Simply a form.«

Now that he’s properly warmed up (hehe). The ice is broken – let’s talk about text.

HA: »That thing about having text and then a vocal line… I mean, actually writing something for the voice was very foreign to me when I was very young.

It wasn’t the text itself that was the problem. Quite the opposite. I’ve been very inspired by text from a very early age. Very early. My very first pieces, actually.

In my early works, what was sung was almost… how can I put it… quite pure. It didn’t really reflect emotions in the music. It was almost like going all the way back to an objective style. And then later, a more expressive way of singing comes in.«

He jumps from his earliest works to poems by Hans Jørgen Nielsen, from Winternacht to words and images used almost like paintings. But letting the text actually carry the music? That was a different challenge altogether.

HA: »I had difficulty connecting text and music in a direct way. And I still do. If I hear a song – it can even be a pop song – I don’t really hear the words when the music is there.«

FH: »So in principle, it could just as well be a clarinet playing it?«

HA: »Yes. It’s like two different halves of the brain.«

Let Me Tell You – Words First

Around 2010/11, Abrahamsen was approached by the Royal Danish Theatre in Copenhagen and asked whether he might be interested in writing an opera. He said yes – with one small condition: it had to be The Snow Queen.

FH: »Had you already started writing some of the music at that point?«

HA: »No, not at all. First of all, I had to write a piece for soprano and orchestra for Barbara Hannigan, which became Let Me Tell You. It was a large piece. In fact, it was the first larger work with text that I had written in a long time. I had done some things back in the seventies – things with text – but this was different. And it was only after that piece that I was supposed to write the opera.«

FH: »Did that give you a bit of a taste for it?«

HA: »Yes. I think I felt that if I could manage to write that piece, then I could also write an opera.«

FH: »And that piece went pretty well.«

HA: »I think what worked for me in Let Me Tell You was that I found a way of combining objective lines – something that is in a way quite objective – with something expressive at the same time. In a sense, it combines opera within itself. It’s somewhat similar to early music: you have the motet. The motet is completely objective, and then a more expressive style is laid on top (Hans demonstrates with his hands). And the two begin to interact.«

So… Where do you start?

FH: »When you actually had to begin writing it, you already had the text, but did you also have an idea of concrete scenes regarding the music? Or was it more a case of starting in the top left corner of the score and just going from there?«

Abrahamsen laughs – and, as if on cue, reaches for the programme book from Dresden. He flips it open and points to a diagram.

HA: »I thought you might go there. I made this very, very early on. All the way back around 2008/9. It’s very old.«

What he shows me is not a sketch for the opera itself, but a structural idea that predates it.

»What I did was take Schnee as a starting point. If you know the piece, it’s built out of pairs of movements: first, two canons of nine minutes each.«

He immediately places it in a historical lineage.

»It’s a bit like Bach – think of the partita movements or Die Kunst der Fuge. You have one movement, and then it comes again in another version. With ornaments, or a different instrumentation.«

FH: »Ah. A variation.«

HA: »Yes. And they’re exactly the same length. Two times nine minutes.«

He continues, counting the form out loud: »Then comes the next pair: two times seven minutes. Then two times five. Then two times three. And finally, two times one minute. And you can see that the form in Schnee becomes slower and slower.«

FH: »That’s the opposite of the first and second acts of The Snow Queen.«

HA: »It’s completely reversed. And that’s purely dramatic. The first and second acts of The Snow Queen actually have exactly the same time structure as Schnee.

But of course, to write an opera, you have to have some kind of form. I can’t just start at one end, because the proportions have to be very large. It all has to hang together – ideas, connections, and so on.«

Ice, Ice, Maybe?

FH: »You’ve written several snow pieces: Schnee, Winternacht, Zwei Schneetänze, and also the Ophelia Songs, all of which somehow involve snow. It’s a bit funny, because in Denmark we don’t really get that much snow anymore. Or… actually, it’s not very funny at all.«

HA: »That’s true. And it’s also present in Winternacht. The first movement starts right in the middle of winter – each section lasts roughly a minute – and then it moves, almost as if through the night. It actually ends in something like spring.«

He pauses, searching for the right image.

Winter music isn’t strange or new in itself, he explains. If you’re a figurative painter, you can paint winter landscapes – and music has done the same for centuries. We already have Vivaldi’s Four Seasons and Schubert’s Winterreise. There’s plenty of winter music. And spring music, too.

FH: »So it’s more the idea of winter in the music – not just the weather? Is winter your favourite?«

HA: »It’s not only winter.«

FH: »You just haven’t written that much rain music or hail music. Or maybe that’s still waiting to happen?«

He smiles.

HA: »Rain music… hail music… I don’t think so. What’s so fascinating about winter is winter itself. There’s something incredibly poetic about the first snowflakes falling – how they drift down, quietly, unlike anything else.«

That, he adds, is exactly how Winternacht began. He whistles the opening softly and traces falling snowflakes in the air with his left hand.

»You hear these short points – almost dots. Very punctual. Like pointillistic music. Webern (he sings softly) dy dyy ding dumm…

And in between those points, there’s silence. (Sings again) dy…(pause) dy… And then, gradually, something begins to form.«

What becomes clear is that snow, for Abrahamsen, is not always something he sets out to illustrate. It begins with sound: lines, whispers, tiny musical dots appearing and disappearing, with silence in between. Only later does the picture click into place – oh, this is snow. Much like Debussy, who added titles to his preludes only after the final double bar.

And snow itself has range. It can erupt into a full-blown storm or lie perfectly still, whitening the world and quietly rewiring its acoustics. It’s precisely that span – and its opposites – that keep pulling him back.

Cool Composing?

As Abrahamsen explains it, Schnee is already embedded in The Snow Queen. It turns out to be one of the opera’s central building blocks.

HA: »When I read The Snow Queen, I could hear it. If you sit down and listen to my pieces, there’s a lot of Schnee. That’s the beginning. And it also appears in the Snow Queen’s palace. That’s Schnee – the first canon.«

The second canon, he explains, is lighter: children playing, snow beginning to dance – the moment when the Snow Queen herself enters.

That same material keeps resurfacing across the opera. The transition between scenes at the end of Act I grows into a full snowstorm. The music returns again in Act III, where Kay and Gerda are attacked by the Snow Queen’s guards and rescued by angels. Even the final scene echoes the innocent second canon from the last movements of Schnee.

And then there’s all the formal connective tissue we talked about earlier – holding everything together.

In short, Schnee runs right through The Snow Queen. Guess, she wouldn’t have it any other way.

But the opera also reaches further back into Abrahamsen’s catalogue.

The song Gerda sings about the evil troll and the shattered mirror comes from a choral piece he wrote as early as 1970, Sangen om os, skoven og Trolden. What sounds almost naïve on the surface turns out to be some of the most complex music in the opera.

HA: »That melody – (sings) da da da – is actually some of the most complicated music in the piece. If you look at the score, there are tempo modulations, and at the same time all those splinters appear, describing the mirror – the shards and everything.«

Large parts of Act I also draw on Märchenbilder. The fast third movement – and especially the transition leading into it – reappears here, along with smaller accelerations and fragments that return later when Gerda sets off.

For Abrahamsen, this has to do with fairy-tale imagery – fitting, he notes, since H.C. Andersen often spoke of his stories as picture books.

Music from some of his piano works surfaces as well. And towards the very end, yet another earlier piece enters the scene.

HA: »The very last thing appears here at the castle. There’s also something from Walden (his wind quintet), something forest-like. It appears there, and again at the beginning of Act III, where it almost takes on a turn that sounds like Der fliegende Holländer.«

Seen this way, the opera begins to resemble a musical network rather than a single, closed work.

FH: »Was it almost as if you knew the opera was coming?«

HA: »That’s exactly why it fits into my universe.«

FH: »So could you almost call it a kind of collage?«

HA: »Yes, you could say that. But if I were a painter, I’d say it’s more about having certain recurring figures or themes. I don’t really think of it as collage – more like having certain kinds of signatures.«

Page to Stage

Andersen wrote The Snow Queen in two very different moods: first, the troll and the mirror, written on a summer day in 1843 near Dresden; then, a year and a half later, the rest of the story, finished on a winter day at Nysø Castle in the south of Denmark, with snow falling outside the window.

It’s exactly the kind of split-screen history Abrahamsen enjoys – patterns, parallels, things written far apart in time that somehow belong together. And right in the middle of that thought, he quietly shifts gears.

HA: »I’ve been writing my… I’m almost finished writing my second opera. It’s based on Karen Blixen’s The Dreamers. There are basically two stories. One is about a man sailing along the African coast, and it takes place in 1863.

And then there’s a kind of prehistory… that takes place twenty years earlier. I like that. When something suddenly connects by coincidence. Then it makes sense to me. And the more things connect accidentally, the more I feel that I’m on the right path.«

There’s a brief pause before it dawns on me what he’s just said.

FH: »I didn’t know that you were working on a second opera. Is it something you’ve been working on for a long time?«

HA: »It’s been written over the past three or four years.«

FH: »So you’re well into it – or almost finished?«

HA: »It’s actually finished. I’m just missing the preludes to the first and second acts. Two short preludes.«

From Mozart to Mid-Air

FH: »Do you have any opera composers you see as role models?«

HA: »When I was writing it, I listened a lot to Rameau. And of course Mozart – I know Mozart’s operas very well.«

Mozart doesn’t just hover politely in the background – he shows up right where things get crowded.

»At the end of the second act, I built a quintet. Isn’t there a famous quintet in the second act of Figaro or something like that? Ensembles, in general – I think they’re fantastic.«

And while there is a quintet, The Snow Queen is very much not a neat little number opera where everyone lines up, sings their bit, and politely waits for applause. The music keeps going – almost no breaks, no clear “now we stop” moments. Through-composed (Hello, Wagner).

HA: »It’s like one big picture. But at the same time, there are these – in much of my early music – actual cuts.«

This is where Stravinsky enters, scissors in hand.

»You can make a transition. Compose a transition. But you can also make a direct cut.«

One of those cuts happens between the third and fourth scenes of Act I, and Abrahamsen clearly enjoys that moment.

»That cut is fantastic – I really like that spot – because it’s an organic cut.«

To explain what he means, he reaches for an image that is anything but abstract.

HA: »It’s like taking off in an aeroplane. You feel it starting. The engine turns on. The forces get stronger and stronger. It goes faster and faster. And then suddenly you leave the ground – and you’re flying.«

As he speaks, he illustrates the take-off with his whole body, nearly ending up horizontal on the sofa.

HA: »And then it becomes quiet. Slower and slower, if you look out the window. It’s fantastic. You don’t fall – you lift off and fly.«

Other Feathers In the Snow

HA: »It’s probably also because there aren’t really ‘numbers’ as such. But you mentioned composers – and yes, of course, there are others. Debussy, for instance.«

Debussy gets a polite nod – then Abrahamsen turns homeward.

He points to two Danish composers with a direct line to H.C. Andersen, both of whom had already tangled with The Snow Queen long before Andersen’s fairy tale ever existed. Andersen had, in fact, written a song called The Snow Queen years earlier – a story closer to Elverskud than ice palaces: a young man on his way to his fiancée is lured away, abducted by the Snow Queen, and disappears.

FH: »Did he also write the melody?«

HA: »No. Carl Nielsen and Niels W. Gade both did – and I actually use both melodies in The Snow Queen.«

Two composers, two melodies – both quietly smuggled into the opera.

And once you start listening for these things, they’re suddenly everywhere.

In the crow scene (Akt III), where Gerda meets the crow who convinces her that the prince might be Kay, Abrahamsen lets two famous birds perch side by side. One is the Danish song Højt på en gren i krage, the other is Schubert’s Die Krähe. Different traditions, same species.

Other music keeps sneaking into the opera – very much on purpose. When Gerda glides in by boat in spring, familiar water figures float up in the score, with friendly flashes of Bach, Schubert, and Beethoven. They don’t take over or turn into quotations; they just pass through, briefly, before sinking back into Abrahamsen’s own sound world.

Lingua Frost – Text and Texture

When Abrahamsen talks about the relationship between text and music, it isn’t only the meaning of the words that matters to him, but also, very concretely, how they can be sung.

HA: »Yes, you have to think about that. Vowels like ‘i’ are actually difficult to sing on high notes. It’s the opposite, really. ‘i’ should be on a low pitch, whereas the dark vowels – if you want to sing high – are ‘o’ and ‘å’. It almost works the other way around.«

In other words: vowels have opinions – and not all of them enjoy the high life.

HA: »You also have to think that singing is almost the same as breathing.«

From there, the conversation turns to language. The Snow Queen was first performed in Copenhagen in Danish, and only three months later at the Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich, in English. A different language means different words – and, crucially, different vowels.

Right in the middle of this explanation, something else happens.

Ella (the cat) jumps up onto a small wall-mounted shelf.

HA: »Well. That was the first time she’s done that.«

FH: »Really?«

HA: »Yes. That was impressive.«

For a brief moment, the opera disappears entirely, replaced by a living room and a very accomplished cat.

Then we’re back.

HA: »But that was because it was originally planned that Barbara Hannigan would sing Gerda in Copenhagen. When she thought about it, she said: ‘I can’t sing in Danish.’ But they had planned it in Munich.«

From the very beginning, Abrahamsen’s ambition was to preserve as much of H.C. Andersen’s original text as possible: »I did that because his language is very, very original.«

After Let Me Tell You, however, he would have preferred the opera to be written in English. That idea was turned down: the Royal Danish Theatre wanted the opera in Danish.

HA: »If you write it in Danish, you really limit which singers can perform it… Danish isn’t exactly an international language.«

The solution became a compromise. The opera was completed in Danish – and then, in a very short amount of time, translated into English for the Munich production.

For that task, Abrahamsen worked with the highly experienced opera translator Amanda Holden, who has translated countless operas from Italian into English, despite not speaking Danish herself.

»I don’t really know how she managed it. She worked with dictionaries, and she also knew an older Danish soprano living in London. I spoke with her a lot during that period. She did an incredibly good translation.«

The obvious question was whether something would be lost in translation – especially when words are closely tied to musical phrasing.

FH: »Didn’t it lose something if you had written a specific word for a specific note or phrase?«

HA: »She’s so experienced. She found the right words that corresponded to the music. There were very, very few places that needed adjustment.«

FH: »So it still fits?«

HA: »Completely.«

What fascinated Abrahamsen most in the process was how the translation handled Andersen’s peculiar turns of phrase. Andersen’s language is already slightly strange – even in Danish. In many English translations, those moments have traditionally been smoothed out. For the opera, Abrahamsen insisted on the opposite: the English should keep a bit of that oddness, rather than ironing it away.

Tragic or happy ending?

The ending of The Snow Queen has been stirring arguments for years – and Abrahamsen knows it. Scholars have been politely disagreeing about it ever since: Is the ending tragic or hopeful? Some read it as a kind of emotional stalemate, where Kay and Gerda return unchanged, adults who never quite grow up. Others insist it’s exactly the opposite.

For Abrahamsen, the point isn’t choosing sides, but holding two ideas at once.

HA: »You can see it in many different ways. You can see it as a happy ending – in the sense that you are reborn in every moment.«

Growing up, in this view, doesn’t mean leaving childhood behind.

HA: »You become an adult, but you remain a child at heart. You keep that childlike openness.«

That way of thinking also reframes the fairytale’s final image – the “eternal summer.”

HA: »And then there’s the eternal summer with the Snow Queen. But she might come back.«

FH: »One can always hope.«

HA: »One can hope.«

Just hours earlier, the sun was shining when I rang the doorbell with its small, homemade sign. By the time I cycled home, bike lights were suddenly essential.

In a few days, I’ll be meeting The Snow Queen in Dresden – live, in all her frosty glory.

- Dialogues des Carmélites, The Royal Danish Opera 2026

- Monster’s Paradise, Hamburgerische Staatsoper 2026

- Dialogues des Carmélites, Semperoper Dresden 2026

- Lohengrin, Staatsoper Berlin 2026

- Das kalte Herz, Staatsoper Berlin 2026

Dialogues des Carmélites, The Royal Danish Opera 2026

If you’re waiting for something to break, Act III is your moment. In Barrie Kosky’s production of Poulenc’s only long opera, it’s not the people – it’s the wall. We’re stuck in the same room. Boxed in by the same walls. First, inside the de la Force family. Then we convert to the Carmelites. Grey…

Monster’s Paradise, Hamburgerische Staatsoper 2026

World premiere! A brand-new opera by Austrian composer Olga Neuwirth. Which basically means: no one knows what we’re about to listen to or experience. No map, no manual, no “how it’s usually done.” What is an opera, anyway? At what point do we decide that something is one? If this hadn’t taken place inside the…

Dialogues des Carmélites, Semperoper Dresden 2026

Did someone say Poulenc? At the Semperoper? For the first time ever with Dialogues des Carmélites? Yes, you heard that right. The French composer’s second opera has found its way to Dresden, in a production directed by Dutch Jetske Mijnssen. The prelude is silent. Curtain up. Blanche is already there, standing alone in a wide,…