“Zu meiner eignen Lust will ich den Kopf des Jochanaan in einer Silberschüssel haben.”

With these chilling words, Salome demands her dreadful prize — a moment of dark beauty and obsessive hunger. Richard Strauss’ opera is a savage, soul-shaking journey, and in Malmö, it came to life in a stark, dust-swept world, where ash clung to the stage and a wall of light towered in the darkness.

As you properly already know, the opera skips the overture and dives straight in with a sneaking, upward run from the clarinet. Before that, however, the orchestra pit is shrouded in darkness, as if holding its breath. Then, a spotlight slices through the shadows, unveiling the young Salome, gracefully moving across the stage. Her red curls tumble freely around her shoulders, and she wears a delicate white dress that seems to glow against the dark backdrop. She appears like a vision of innocence, yet something unsettling hangs in the air, as if a storm is quietly gathering on the horizon.

As the focus shifts, the clarinet begins to climb slowly, almost languidly, up the motif that, as the drama unfolds, will become Salome’s. The tempo, perhaps the slowest I’ve ever encountered, stretches the music into a journey of its own — a path where the movement from one note to the next isn’t just about reaching a destination, but about savoring every step along the way. Each tone in the ascent is drawn out, emphasized, as if it too is caught in a moment of reflection.

The orchestra itself is as transparent as glass, letting every small detail shine through. Even the smallest musical gestures — a soft string passage or a brief woodwind phrase — floats almost independently in the air. However, at times, the sound seems like it might lose its connection, as though the instruments are pulling in different directions. On the other hand, this creates a great opportunity to hear Strauss twisting and turning his motifs, almost as if he’s tossing them up in the air and letting them land in unexpected shapes. It’s a constantly shifting and lively landscape.

The Power of Salome

When Salome premiered in 1905, it sparked both excitement and scandal. Imagine the audacity – the idea that a woman could actually have desires! Gasp! Strauss’ explosive music and the opera’s unapologetic portrayal of lust and death shook things up, especially with Freud’s fresh theories on the unconscious lurking in the air. The opera was banned in several places, but it powered through the uproar and remains a staple on the repertoire today. Over a century later, Salome still has the power to shock – and if it’s not the music or the drama, then perhaps the final scene, with Salome kissing Jochanaan’s severed head, might just leave you feeling a little queasy.

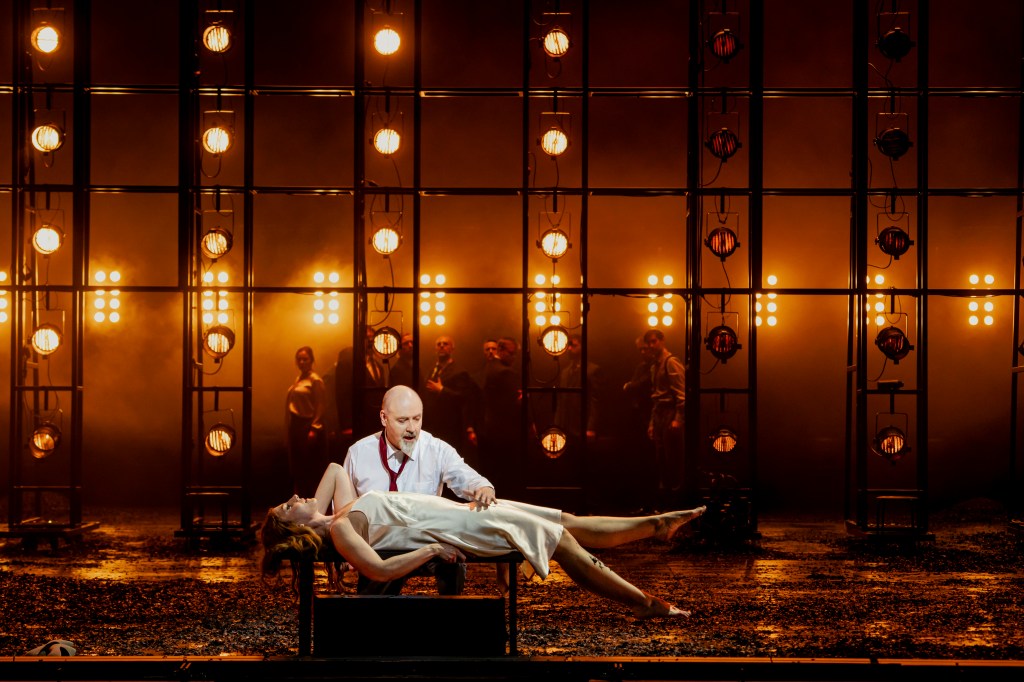

Before we get to the decapitated head, we’re introduced to the man behind it — and it happens with a bang. Jochanaan makes his entrance, and we’re all dazzled. By his divine aura? Well, not exactly. But by the giant wall of lights standing in the middle of the stage, glowing like some sort of religious revelation.

From the moment Salome hears the prophet’s voice, she’s captivated and wants more. The guard, Narraboth, who, like a certain other character, is deeply fascinated by Salome, ends up (despite his orders) letting her see Jochanaan. He also kicks off the whole opera with the words “Wie schön ist die Prinzessin Salome heute Nacht!” which he delivers to Herodias’ page, who’s sung with a rich, smooth tone by Mathilda Bryngelsson.

But Jochanaan isn’t exactly throwing himself at Salome. He doesn’t even want her to touch him. Or does he? Even though he tells her to go away, there’s something strange about how he can’t quite take his eyes off her… A little fascination slipping through the cracks, perhaps?

That´s Wilde

It’s almost a Wilde coincidence how perfectly Laura fits the role of Salome. Not only because she shares a last name with Oscar Wilde, the brain behind the narrative, but also because that name somehow seems to echo the very audacity of the character herself. And, fortunately, the American soprano captures that confidence with captivating clarity.

Salome is no easy feat — it requires not just a dazzling upper register but also a deep, resonant foundation, and Wilde delivers both in spades. As she spirals downward, each note glows with a rich, mezzo-like warmth, effortlessly weaving together power and subtlety. The notorious plunge on the word “Jochanaan” from a bright B♭ to an octave and a fifth lower — a moment that could easily end with a burp — instead emerges with pure clarity, as smooth and natural as though it were the most effortless thing in the world. Her tone in the higher registers never cuts or pierces but retains a soft and (relatively) round sound.

Dance of the Seven Veils

At the premiere, Marie Wittich (Salome) refused to undress during this orchestral interlude. Standing naked on stage? Not exactly your typical Tuesday night performance back then!

Tonight, however, there was no hesitation. After all, the only thing shed was a simple gray cardigan. While the dance itself wasn’t the extravagant, seductive performance you might expect, the true surprise came from an unexpected change in the staging. The previously still and static set began to rotate, adding a dynamic visual element as the singers moved across the stage. Meanwhile, King Herod remained seated in his grey suit, his back to the audience, and completely absorbed in the spectacle.

Herod’s role was brought to life by Michael Weinius who not only (jumped in last minute but also) showcased his vocal prowess and subtly conveyed the awkward and unsettling nature of the character.

The opera reaches its conclusion with one of the quickest death scenes in operatic history. Herod, almost drowned out by the orchestra’s powerful crescendo, utters the chilling line, “Man töte dieses Weib!,” followed by the final, thunderous blows in the music. We don’t see Salome’s death, though, as the massive light wall blinds us one last time, leaving us in darkness.

Fun Fact:

In 1945, when American troops arrived at Strauss’ villa in Garmisch, he simply said, “I am Richard Strauss, the composer of Rosenkavalier and Salome.” Luckily, Major John Kramer, a huge Strauss fan, quickly put up an “Off Limits” sign on the lawn. Later, when soldiers inspected his house and kept asking about a statue of Beethoven, Strauss muttered, “If they ask one more time, I’m telling them it’s Hitler’s father.”

Trailer:

Cast:

- Conductоr: Patrik Ringborg

- Directоr: Eirik Stubø

- Stаge Designer: Magdalena Åberg

- Сostume Designer: Magdalena Åberg

- Light Designer: Ellen Ruge

- Choreography: Örjan Andersson

- Salome: Laura Wilde

- Herodes: Michael Weinius

- Herodias: Karin Lovelius

- Jochanaan: Kostas Smoriginas

- Narraboth: Conny Thimander

- Herodia’s Page: Mathilda Bryngelsson

- Jewish Scholar: Carl Rahmqvist

- Jewish Scholar: Tor Lind

- Jewish Scholar: Rickard Söderberg

- Jewish Scholar: Fredrik Hagerberg

- Jewish Scholar: Joel Kyhle

- Nasaré: Magnus Lindegård

- Nasaré: Darko Neshovski

- Soldier: Caspar Engdahl

- Soldier: Gustav Johansson

- A Cappadocian: Philip Christensson Gerrard

- A Slave: Laine Quist

Malmö Operaorkester