Before we even get the chance to settle in – before the lights dim or the conductor makes his grand entrance – the evening’s so-called “national music drama” is already underway. Not with a bang, nor with Mussorgsky motif, but with a deep, echoing rumble that seeps from the speakers like the breath of a sleeping beast.

It sounds less like an overture and more like a warning. We’re not in the theatre anymore – we’re in a cave. Or a bunker. Or maybe the echo chamber of a crumbling empire?

From the left, a woman wrapped in a headscarf shuffles onto the stage. The massive golden curtain rises… only to reveal another curtain. And then another. A scenic matryoshka, unfolding layer by layer. Tsarist Russia, here we go.

It’s Easter, and that means it’s time for Salzburg’s Osterfestspiele (Salzburg Easter Festival)! This year, the program features Modest Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina.

The opera he never got to finish before his life was cut short at just 42 – thanks to a love affair with vodka.

What he left behind were fragmentary sketches and no piano score for the final two scenes. Several composers have since tried to complete the puzzle. The first to roll up his sleeves was Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Then Maurice Ravel and Igor Stravinsky popped in with their own contributions. Fast forward 75 years after Mussorgsky’s untimely exit, and Shostakovich jumped in with a version for a film adaptation. That’s the one that’s most commonly used today, often accompanied by Stravinsky’s grand choral finale!

All of which means the music is, to some extent, fair game. In Salzburg, they’ve even cut and pasted the score here and there—like a musical collage. Why not? When the composer never closed the book, it’s tempting to keep turning the pages your own way.

Director Simon McBurney takes full advantage of this creative freedom, teaming up with his brother, composer Gerard McBurney. It’s Gerard’s electronic soundscapes that kick off the evening – not Mussorgsky’s – and they weave in and out of the opera like ghostly interludes, shaping the atmosphere.

How does it sound in a cave? Or in a forest? Gerard answers with shimmering textures, distant echoes, and birdcalls that feel more like sonic hallucinations than nature documentaries. The result is a world that hums, breathes, and occasionally shivers – just like the unstable Russia it depicts.

Modest’s Music

Mussorgsky’s prelude lifts instantly, the violas rise, their motion caught by the violins, which soar higher, their flight caught and carried by the bright flutes. A clarinet lets loose a melody, as tremolo strings flutter beneath – like light breaking through the first crack of dawn.

On stage, a great golden circle slowly rises, spilling its light across the scene like the first rays of a new day. But this sunrise doesn’t bring peace—it brings clarity. As the light spreads, it reveals a battlefield, soaked in blood, with lifeless bodies strewn like discarded dolls. The fight is over—or so it seems…

What do you get when you mix political disagreements, unlikely alliances, and a botched assassination attempt? Sounds like today’s headlines, right? But it’s also the plot of Khovanshchina.

Prince Ivan Khovansky, the Muscovite Streltsy and the ultra-conservative Old Believers aren’t exactly thrilled about regent Sofia and the young Tsars Peter the Great and Ivan V trying to Westernize Russia. So, they join forces, start a rebellion, and everything quickly goes up in smoke—literally. As betrayals mount, executions loom, and a failed drowning attempt leaves more than one life hanging by a thread, the Old Believers decide they’d rather light their own fire than surrender. Grim? Yes. Grand opera? Absolutely.

At the Bottom

If you’re into deep, rumbling voices that feel like they’re coming from the core of the earth, this one’s for you. In Khovanshchina, it’s the lower registers that rule the stage.

Ukrainian bass Vitalij Kowaljow brings Prince Ivan Khovansky to life with a voice that’s rich, resonant, and gloriously thunderous. And he doesn’t just sound the part—his stage presence packs just as much punch.

Also standing out is Russian mezzo-soprano Nadezhda Karyazina, who absolutely owns the role of Marfa. Her voice is rich and full, sweeping through the lower registers while still maintaining a bright, cutting clarity in the higher ones.

Marfa is a woman who’s tough as nails but also has her messy, tender side, especially when it comes to her love for the far-from-perfect Andrei Khovansky. Yes, you heard that right – in this opera, the tenor isn’t the hero!

Screens, Shadows and Symbolism

The staging pulls elements from two different worlds. One moment, you’re in old Russia, but then, out of nowhere, there’s a laptop, and yes, they also smash a phone. A comment on contemporary society, perhaps?

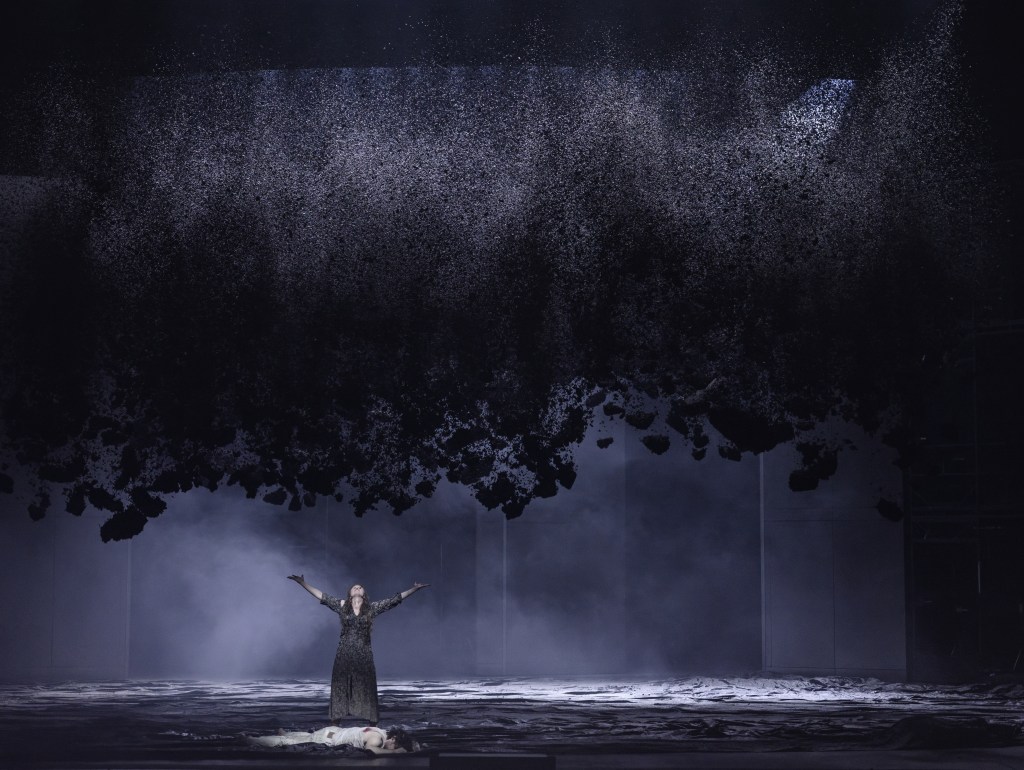

The production keeps props to a bare minimum and instead plays with shifting spaces. Metallic walls glide in and out, sometimes closing in like the drama itself—tight, tense, and inescapable.

It manages to conjure up some striking imagery: just take the haunting shadows in Act 4, cast across the back wall, turning a bare stage into something almost cinematic.

As for Esa-Pekka Salonen and the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, there’s really not much to fault. The atmosphere was charged, and with Salonen’s cool control and gliding gestures, he steered the music through a series of tempo shifts as smoothly as changing gears in an electric car—completely automatic.

He brought out delicate solos and, in the quieter passages, the playing felt effortlessly smooth and natural—like a seamless flow, never forced. The orchestra followed him with such precision, making each change in mood feel completely organic.

Fun Fact:

The two-finger cross you see in the production? In 17th-century Russia, some believed the Orthodox Church had drifted too far from its original traditions. As part of a series of reforms, they introduced changes like switching from a two-fingered to a three-fingered cross. This sparked a split within the Church, known as the Raskol, as many followers rejected the changes.

The Cast:

- Conductor: Esa-Pekka Salonen

- Director and chorograph: Simon McBurney – Choreographie

- Stage Director: Rebecca Ringst

- Costume Designer: Christina Cunningham

- Lightning Designer: Tom Visser

- Videodesign: Will Duke

- Dramaturg: Gerard McBurney and Hannah Whitley

- Sounddesign: Tuomas Norvio

- Fürst Iwan Chowanskij: Vitalij Kowaljow

- Fürst Andrej Chowanskij: Thomas Atkins

- Fürst Wassilij Golizyn: Matthew White

- Schaklowityi: Daniel Okulitch

- Dosifej: Ain Anger

- Marfa: Nadezhda Karyazina

- Ein Schreiber:Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke

- Emma: Natalia Tanasii

- Warssonofjew: Rubert Grössinger

- Susanna: Allison Cook

- Kuska: Theo Lebow

- Streschnew: Daniel Fussek

FINNISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTER

Slowakischer Philharmonischer Chor

- Jan Rozehnal

Bachchor Salzburg

- Michael Schneider

Salzburger Festspiele und Theater Kinderchor

- Wolfgang Götz and Regina Sgier