It’s winter, and the cold is creeping in—a perilous season for singers. This evening offered more drama than expected when a lady stepped forward before the opera began. That can only mean one thing: a cast change. The question is, which warrior has fallen?

Turns out, one of the singers wasn’t feeling at their peak but chose to brave the stage regardless. A daring move that left us all waiting to see if the gamble would pay off. (And funnily enough, the same drama unfolded last weekend at Deutsche Oper Berlin’s Macbeth!)

Never before had a composer been paid more than Giuseppe Verdi for Aida—150,000 gold francs (whatever that amounts to) just for the Egyptian premiere, which took place on December 24, 1871. Fittingly, this is also where the opera’s story officially unfolds.

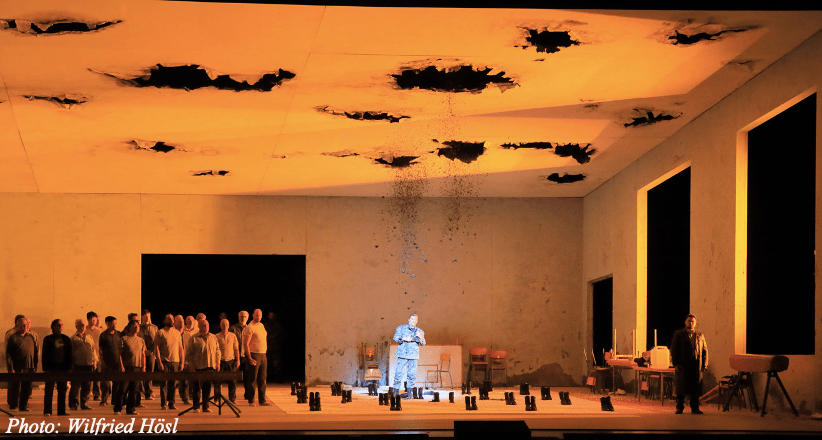

Perhaps we’re in Egypt tonight as well—or maybe not. It’s hard to tell, as the only setting we see is a half-empty gymnasium with pale blue walls and ceiling holes, seemingly left behind by bombs. We’re clearly in a war zone. The characters show little trace of joy, remaining almost entirely miserable from start to finish.

In the first two acts, ash occasionally gently fall from the ceiling, its descent growing more dramatic as side lighting casts long, menacing shadows. This sets the stage as returning soldiers limp forward to receive their medals—not to cheers, but with hesitant steps, crutches, wheelchairs, and missing limbs bearing silent witness to the cost of war.

The scene grows even heavier when a semi-transparent screen flickers to life, displaying haunting images that plague Radamés. War is a monstrous beast, and it’s no wonder these soldiers aren’t exactly leaping for joy, even with victory in hand. The triumphant blast of the six Aida trumpets on the balconies almost feels like a cruel irony, their majestic sound clashing with the weight of pain that lingers in the air. It almost feels like they’ve wandered in from another world.

In the final two acts, a half-mountain made of rubble has been formed in one corner of the gymnasium, seemingly the aftermath of a bombing. Several characters take turns sitting there, each one showcasing their own misfortune.

The acting, however, feels restrained. While the characters’ struggles are apparent, their emotions remain somewhat muted. Much of the singing is directed toward the audience rather than between the characters, which makes the interactions feel less dynamic and the dialogue more limited.

The evening is certainly carried by the strong cast. Elina Garanča shines as Amneris, her rich voice and beautiful tone standing out throughout the performance. Erwin Schrott as Ramfis—who, as it turns out, was the one who wasn’t feeling quite at his best. I have to say, though, I didn’t notice any difference from his earlier performances. Amartuvshin Enkhbat took on the role of Aida’s father, Amonasro, with a commanding presence. Then there’s the evening’s Romeo and Juliet, aka Radamés and Aida, played by Arsen Soghomonyan and Elena Stikhina—both of whom have fine voices.

Down in the pit, Francesco Ivan Ciampa kept a steady hand on the orchestra, though his rather swift accelerando just before the break made me wonder if he was eager to hurry us all to intermission.

One of the things I admire about Verdi is his masterful use of the choir, both on and off stage. There’s nothing like the power of a big choir, and a standout moment from the first act showcases this perfectly. The choir slowly enters from the left, while light streams in from the opposite side like a sunset. Their cautious steps and gentle singing create an atmosphere so captivating exactly like reaching for just one more piece of candy—you can’t help but crave a little more.

The cast delivered strong performances, though the acting was rather minimal. The staging, with its gymnasium-like space and piles of rubble, reinforced the opera’s tragic tone. Unfortunately, the visuals didn’t offer much to captivate the eye.

Fun Fact:

Verdi introduced a unique instrument for this opera: the Aida trumpet, a sleek, straight brass instrument with just a single valve.

Trailer:

Cast:

- Conductor: Francesco Ivan Ciampa

- Director: Damiano Michieletto

- Stage Designer: Paolo Fantin

- Costume Designer: Carla Teti

- Video: rocafilm

- Choreography: Thomas Wilhelm

- Licht: Alessandro Carletti

- Choir: Christoph Heil

- Dramaturg: Katharina Ortmann and Mattia Palma

- Amneris: Elīna Garanča

- Aida: Elena Stikhina

- Radamès: Arsen Soghomonyan

- Ramfis: Erwin Schrott

- Amonasro: Amartuvshin Enkhbat

- Der König: Alexander Köpeczi

- Ein Bote: Zachary Rioux

- Eine Priesterin: Elene Gvritishvili

Bayerisches Staatsorchester

Bayerischer Staatsopernchor und Extrachor der Bayerischen Staatsoper