We’re all going to die. That’s the only thing we can be sure of. But how? See, that’s a real mystery. Doomsday is lurking around the corner. It could be tomorrow, in 10 years or maybe in 500 years. Who knows? In György Ligeti’s wild and chaotic opera – or an “anti-anti opera” as he described it – Le Grand Macabre, we catch a glimpse of one apocalyptic scenario.

Krzysztof Warlikowskis’s production of the opera premiered this summer at the Munich Opera Festival and has once again tasted the polished floors of Bayerische Staatsoper.

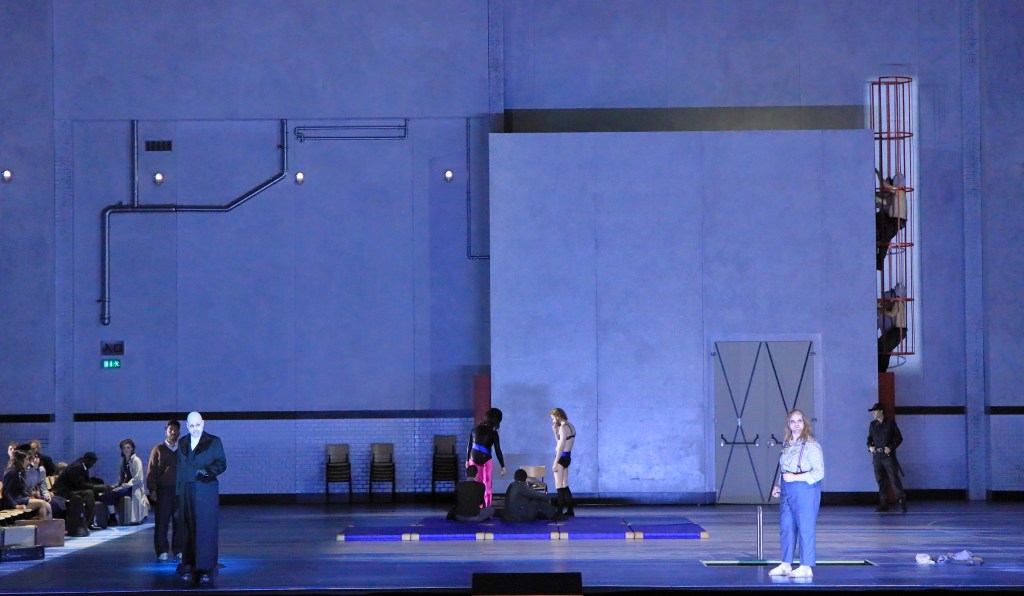

The evening kicks off with an open stage. The curtain has already risen as the nicely dressed audience trickles into the grand hall, stretching five levels high. The stage is caged, and off to the right, a man in a black cowboy hat snoozes peacefully. Only illuminated by the soft blue glow of the computer in front of him. At first glance, it seems like we’ve stumbled into a peculiar blend of a train station and a gymnasium.

On stage, we meet the booze-soaked Piet, clad in an oversized red jacket and grey trousers that are pulled up far too high, barely held up by his suspenders. Shortly after, we bump into Amanda and Amando – whose names make it easy to remember they’re a couple, much like Papageno and Papagena from The Magic Flute. The pair is on a quest for a little privacy when they stumble upon the grave that Nekrotzar has just clawed his way out of. Nekrotzar promptly makes Piet his slave and proclaims that the end of the world is barreling toward them like an unstoppable storm.

It’s Absurd

If I had to sum up the evening with one word, it would undoubtedly be “absurd.” Right from the start, we’re thrown into an absurd world, driven by raw instincts, wild impulses, and a deep-seated fear of death. Absurdity reigns in the music as well, which kicks off with twelve car horns and features instruments like doorbells, various whistles, sirens, Japanese temple bells, a metronome, and even a tray full of crockery, just to name a few. The percussionists have quite an eclectic toolbox at their disposal!

It’s also absurd that Nekrotzar thinks he can waltz into the world with the sole intention of wiping it all out along with everything it offers. What’s even more absurd is the end where he (spoiler alert) dies of sorrow because his only mission has crumbled into dust.

The last absurdity I want to highlight is the vocal parts, which present a big medley of everything. You’ll find spoken dialogues, a kaleidoscope of colourful falsettos and playful onomatopoeic sounds. On top of that, the singers dive into some pretty wild coloraturas and a wide vocal range – stretching from the deepest growls to high-pitched squeaks. The combination of the length and the slightly silly lyrics, which could easily just be “lalala,” brings a playful punch. Although many elements of the opera lean toward seriousness, it’s all wrapped in a cosy sweater of humour that, at some points, also had me grinning. The comedic flair is cranked up even more by the costumes, featuring everything from 80s disco workout gear to bandages from cosmetic surgeries and outfits that give the illusion of being stark naked.

Reality Isn’t Much Rosier

Ligeti was only 16 when the shadows of World War II began to loom over Europe. Several of his closest family members died in concentration camps, and it wasn’t until 1956 that he escaped from Budapest, fleeing the invasion of the Soviet communist regime and its oppressive dictatorship. Ligeti has claimed that such events have left their mark on his music.

The opera had its premiere at the Royal Swedish Opera in Stockholm in 1978. It later returned to the spotlight with a revised version in 1996. This summer marked the opera’s Munich debut. The work consists of two acts, running for about 110 minutes without an intermission.

The orchestra clangs and clatters – thankfully in the best possible way. Kent Nagano, their former General Music Director, now based in Hamburg, skillfully steered us through the absurd score. I especially appreciated some of his crescendos and those sudden, sneaky subito pianos.

If everything falls apart, you can always turn to alcohol. Or? Things kick off with Piet, who stumbles in slightly tipsy and hiccupping, setting the tone for the show. In many ways, this character reminds me of Mime from Wagner’s The Ring of the Nibelung – unpredictable, insecure, and a little quirky. Tenor Benjamin Bruns brings Piet to life in this production. I particularly enjoyed the scene where he and Astradamors, sung by Sam Carl, drunkenly roll around on office chairs, fully convinced they’ve died because of the comet that has just hit the planet earth. A white canvas illuminated by a projector reveals how this unfolds, leading the two characters to believe they are ghosts in the afterlife. Sam Carl has a nice voice, but he only seems to shine in his higher mid-range register.

Surprisingly, the opera offers a bit of a happy ending, with everyone coming together for a drink. Musically, it winds down with an extended diminuendo, gradually fading into a hushed silence.

Trailer:

Fun Fact:

Ligeti has a flair for extreme dynamics. In Le Grand Macabre, it’s not uncommon to stumble upon markings like ffffffff

Cast:

- Conductor Kent Nagano

- Director Krzysztof Warlikowski

- Stage Designer Małgorzata Szczesniak

- Lighting designer Felice Ross

- Video Kamil Polak

- Choreography Claude Bardouil

- Choir Christoph Heil

- Dramaturg Christian Longchamp and Olaf Roth

- Nekrotzar Michael Nagy

- Gepopo and Venus Sarah Aristidou

- Piet vom Fass Benjamin Bruns

- Amanda Seonwoo Lee

- Amando Avery Amereau

- Prince Go-Go John Holiday

- Astradamors Sam Carl

- Mescalina Lindsay Ammann

- Ruffiack Andrew Hamilton

- Schobiack Thomas Mole

- Schabernack Roman Chabaranok

- White Minister Kevin Conners

- Black Minister Bálint Szabó