It all begins in darkness – like the world itself. Slowly, shapes start to take form, while a deep E-flat emerges from the basses, marking the beginning of the world. Faint at first, the sound swells and ripples as the bassoons weave in a fifth, followed by the horns, whose soaring lines break the E-flat major triad like a phoenix rising from the ashes. The atmosphere thickens, growing grander and more powerful, wrapping the audience in an intoxicating embrace.

Then, like beams of sunlight piercing through the depths of a lake, the radiant Rhinemaidens burst onto the scene, their voices ringing out in a shimmering chorus of “Weia! Waga!” After 136 measures, the music simmers with tension, gripping the air like a predator poised to pounce, as they utter the word “gold” hinting at the looming conflict.

This is how Richard Wagner’s 16-hour epic music drama, The Ring of the Nibelung, begins. Twenty-six years in the making, four operas, three evenings, and a Vorabend. A work destined to leave an unforgettable mark on the history of music.

Das Rheingold, the first in the cycle, premiered in 1869 at the very same theater where I heard it tonight: Munich’s National Theater, home of the Bavarian State Opera. Wagner later premiered three more operas here: Die Walküre, the next in the Ring cycle, Tristan und Isolde, and Die Meistersinger – making it an ideal place to take in Wagner’s wondrous verses.

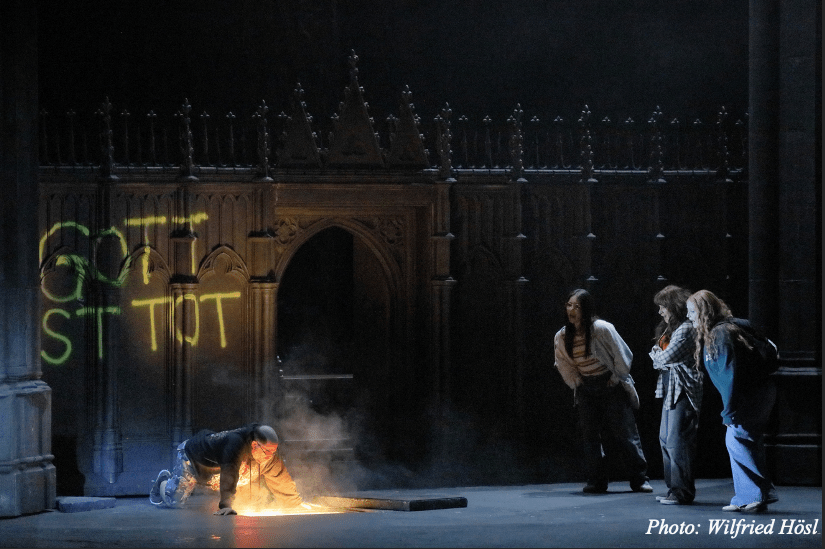

At its core, the opera tells a tremendous tale of the clash between love and power. As the Vorspiel unfolds, we encounter Alberich, a downtrodden dwarf drowning in despair, grappling with the weight of hopelessness. The scene is set in a dimly lit Catholic church, where bold graffiti defiantly proclaims “Gott ist tot” (God is dead). With a trembling gun in hand, he aims it at his temple, caught in the grip of his own anguish, unable to pull the trigger.

Just then, the playful Rhinemaidens burst in, their laughter ringing out like chimes. Alberich tries to win them over, but it doesn’t work, and in his frustration, he steals their glittering gold, giving up on love in the process. As he makes his getaway, one of the maidens is shot in the thigh.

Behind this production stands the upcoming opera director in Hamburg, Tobias Kratzer, who has been making quite a name for himself with frequent performances in various opera houses. He also directed the powerful Tannhäuser I covered last summer in Bayreuth, and his staging of Die Passagierin is soon again on the program in Munich.

Modern twist of tradition

Kratzer’s interpretation of Das Rheingold is a production that blends multiple worlds. In the last two Ring cycles I’ve seen, I’ve missed some of the original artifacts, such as Wotan’s spear, the tarnhelm, Donner’s hammer, and the ring itself. All of this and more is present here. The costumes have a flair for ancient Norse vibes; Wotan struts around in a cloak, a horned helmet, and brandishing a spear – a look that screams “all-powerful god!” But hold onto your helmets, because when he heads down to Nibelheim, he has to trade his divine ensemble for a rather dull blue suit, leaving his godly glamour behind.

At first glance, this might sound like a traditional production, but don’t be fooled – it’s anything but ordinary. The Rhinemaidens, for instance, zip around filming on their phones, while Loge struts about with headphones on. But by blending in classical elements, Kratzer finds a way to engage even those who aren’t the biggest fans of regietheater.

Nibelheim

The lurking Loge and the wily Wotan make their way down to Nibelheim, eager to snag the Rhine gold. Back in the divine realm, the church altar has undergone a serious makeover. Wotan has roped in two giants, Fafner and Fasolt, promising them Freia as their reward. But that, of course, is out of the question. So, Wotan and Loge opt for a little heist to swipe the shiny gold straight from Alberich’s grasp.

Alberich and his brother Mime are holed up in a garage, rifles lining the walls and codes flashing on the computer as they plot their grand scheme for world domination. With the power of the gold, Alberich has whipped up a helmet that lets him morph into any form he pleases. He shows off by conjuring a massive worm that dispatches Mime’s poor, defenseless dog. But Loge, ever the trickster, cunningly convinces Alberich to turn into a little frog, then quickly scoops him up in a lunchbox for safekeeping.

The journey to Valhalla unfolds on a giant white screen that dominates the stage. After navigating a few bumps at security, they finally make it to their flight. Wotan sits proudly, showing off the slimy frog in a transparent container to his seatmate, whose expression clearly communicates his thoughts on this rather quirky character.

The two seized all of the now naked Alberich’s gold, and with just a flick of his finger, Wotan forged a future that was as fragile as it was formidable.

A Little Hint from a Grand Figure

Alberich kicks off the opera by spray-painting “Gott ist tot” in graffiti, but the god – Wotan – is far from dead. The two giants, depicted as priests, help to illustrate this point. They even hold up a sign proclaiming, “Dein Walhall, Dein Wotan.” They reminded me of those street preachers who enthusiastically hand out pamphlets for a “Free Bible Course.”

Is it just a coincidence that the quote “God is dead” pops up in this production? I think not! Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche crossed paths with Wagner just a year before the opera premiered in 1868. For a time, he and Wagner were pretty close. He even attended the premiere of the entire Ring cycle at the first Bayreuth Festival in 1876. But things took a turn, and their relationship soured, leading Nietzsche to change his tune on Wagner. Before that falling out, though, Cosima, Wagner’s wife, noted in her diary that Wagner regarded Nietzsche as “the only living person, apart from Constantin Frantz, who has provided me with something, a positive enrichment of my outlook.”

The Music!

I can’t forget to mention the musicians who truly brought the opera to life! There’s little to criticize here. American bass-baritone James Brownlee filled the role of Wotan with a rich, beautiful tone, while Ekaterina Gubanova, as his wife Fricka, once again impressed me with her delightful performance. Matthew Rose’s powerful voice resonated as Fasolt, and Wiebke Lehmkuhl brought Erda to life with her clear, rounded sound.

Throughout the opera, Erda glides mysteriously across the stage, and when she finally reveals herself, she adorns the ring. With her cautionary words and a revolving set, we see in slow motion how events will unfold if Wotan refuses to surrender the ring to the giants. Behind the altar of a burning church, the giants Fafner and Fasolt have captured Freia, signaling the dark day that gradually dawns on Wotan. Ultimately, Erda unravels time, compelling Wotan to relinquish the ring. This ring, a twisted circle of greed, becomes a metaphor for the inescapable cycle of desire and destruction.

The performances of Alberich and Mime, portrayed by Markus Brück and Matthias Klink, added further depth to this compelling narrative.

On the podium were Vladimir Jurowski, the general music director of the orchestra since 2021. He knows the musicians and the venue well, and it shows in the performance. The orchestra swelled like a mighty river, carrying the audience on a tumultuous journey through love and power. I especially enjoyed the entrance of Fafner and Fasolt and how Jurowski made the music feel grand and pompous – just as towering as the giants themselves. However, I found that he launched into the Vorspiel a bit too abruptly and with a bit too much force for my liking. I had hoped the deep E-flat would gradually fill the space, but his strong start limited the crescendo he could develop. Still, I appreciated his interpretation, which brought excitement and kept the action moving forward, as it should.

A peculiar percussion instrument

Wagner’s opera showcases a unique instrument: 18 tuned anvils that bring the blacksmiths’ theme to life. At the Bayreuth Festival, they still use the real deal, but let’s be honest – they’re not the loudest instruments in the orchestra. I remember feeling a bit let down by their sound during my visit. However, tonight was a different story! Amplifiers around the hall truly brought the anvils to life, creating an immersive experience that made it feel like the blacksmiths were hammering away all around us. The only catch? Without any actual blacksmiths in sight, the sound ended up being a touch overwhelming.

Another standout element of the performance was the harps – and I mean that in the best way possible. Positioned at audience level in two small boxes on either side, their sound sparkled brilliantly through the orchestra when we first heard the Valhalla theme. It created an incredible effect.

Bayerische Staatsoper has joined forces with Tobias Kratzer to bring a complete Ring cycle to life over the next three seasons, and I’m buzzing with excitement to see it!

Trailer:

Fun Fact:

The story goes that in 1871, Nietzsche sent a piano piece to Wagner’s wife, Cosima, as a birthday gift. While she played it with Hans Richter, Wagner slipped out – and was soon found laughing on the floor.

Cast:

- Conductor: Vladimir Jrowski

- Production: Tobias Kratzer

- Stage and Costume Designer: Matthias Piro

- Lighting Designer: Michael Bauer

- Video Designer: Manuel Braun, Jonas Dahl and Janic Bebi

- Dramaturg: Bettina Bartz and Olaf Roth

- Wotan: Nicholas Brownlee

- Fricka: Ekaterina Gubanova

- Loge: Sean Panikkar

- Donner Milan Siljanov

- Froh: Ian Koziara

- Alberich: Markus Brück

- Mime: Matthias Klink

- Fasolt: Matthew Rose

- Fafner: Timo Riihonen

- Freia: Mirjam Mesak

- Erda: Wiebke Lehmkuhl

- Woglinde: Sarah Brady

- Wellgunde: Verity Wingate

- Floßhilde: Yajie Zhang

Bayerisches Staatsorchester